Introduction:

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the devastating effects of resource scarcity in healthcare systems. This emphasises the need to understand and ease Healthcare System Pressure (HCSP). While there’s no official HCSP definition, the Office of Health Economics (OHE) has developed and examined a conceptual framework for HCSP. It includes a broad definition and concepts of HCSP, strategies to lessen HCSP, and a system for metric categorisation.

Understanding Healthcare System Pressure:

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems were feeling the strain. This is evident in the UK, where increasing waiting lists and treatment times are common. Yet, the term ‘pressure’ lacks a clear definition in the healthcare context. When healthcare systems face strain, they behave differently than in normal conditions. This strain could lead to an inability to provide emergency care or delay planned care. Moreover, the quality of care might suffer due to continuous pressure on staff. This can lead to staff burnout and poorer health outcomes for patients.

The Conceptual Framework of HCSP:

The primary exposure of hospital settings to increased patient demand in the event of seasonal diseases or pandemics was the driving force for the decision to concentrate on HCSP in hospital settings. It was the findings of the review that served as the basis for the construction of each individual component of the conceptual framework. They also conducted a ‘proof-of-concept’ exercise utilising expert interviews from Germany, Italy and the UK to test the comprehensiveness and usefulness of this framework, using respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections as case studies.

Universally Accepted Definition of HCSP:

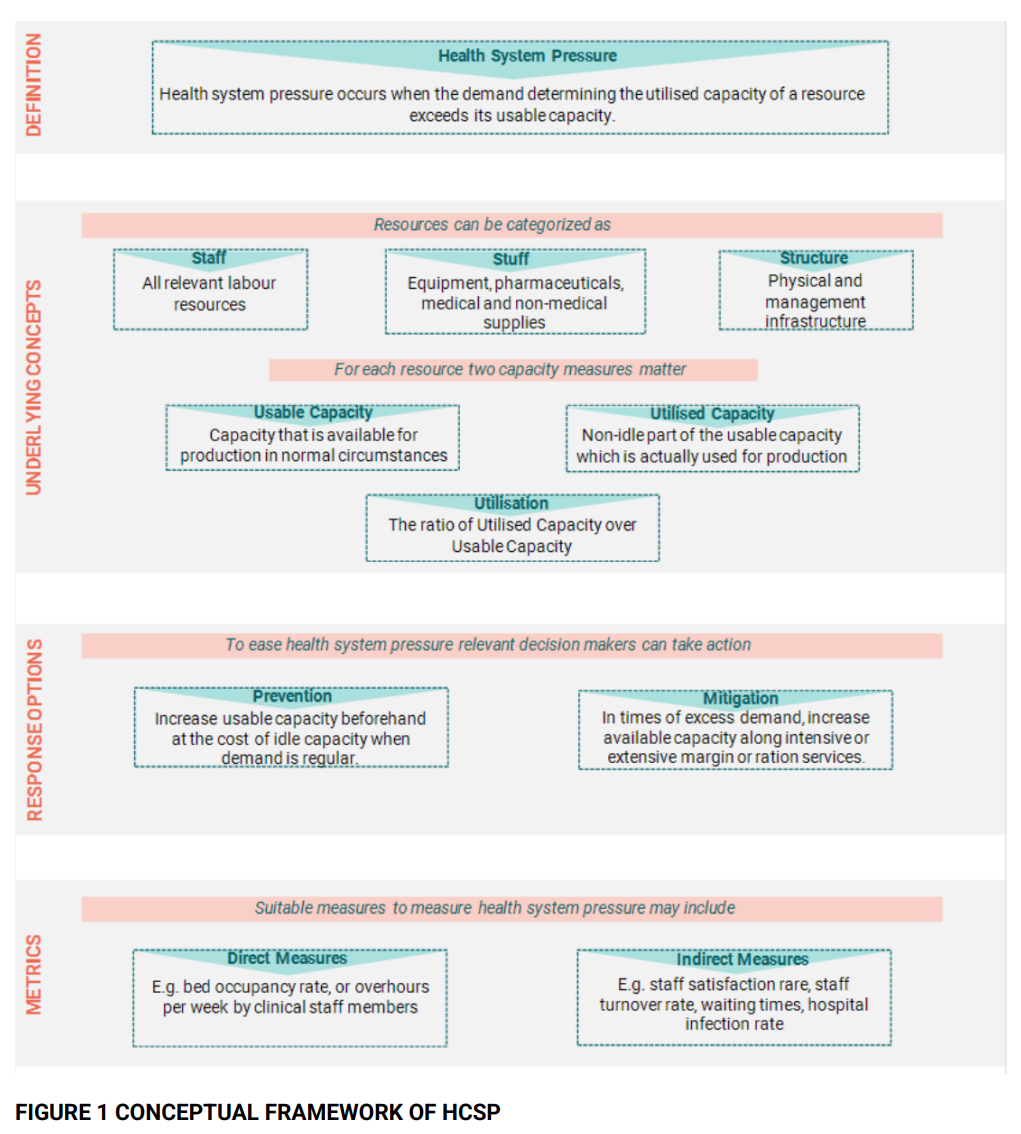

HCSP can affect different types of resources that can be categorised into ‘staff’ (i.e., labour resources), ‘stuff’ (i.e., durable equipment) and ‘structures’ (physical infrastructure within the hospital). A resource has a usable capacity, which is the amount of capacity available for production in normal circumstances. The usable capacity can be split into utilised capacity, which is actually used for production, and idle capacity, which remains unused. Using the concepts of resources, capacity, and utilisation, HCSP can be described as occurring when the demand determining the utilised capacity of a resource exceeds its usable capacity (Figure 1).

Alleviating HCSP:

Keeping bed occupancy below 85% is crucial for hospitals to operate safely and effectively, as seen in the English National Health System (NHS). This framework identifies two main actions to alleviate HCSP: increasing the usable capacity to accommodate higher demand levels and expanding the usable capacity as a pressure-mitigating action. These actions are linked to the concept of surge capacity, which is predominantly applied within the field of disaster management.

Classifying HCSP Metrics:

The OHE found no consensus on the metrics of HCSP and its opportunity costs. However, for each resource, HCSP can be measured using usable and utilised capacity metrics. Routinely collected key performance indicators (KPIs) in hospital finance, procedures, and staff provide multiple pressure measurement alternatives. Some KPIs directly measure resource utilisation (e.g. bed occupancy and average length of stay), while others indirectly indicate pressure (e.g. staff turnover or waiting times). This can impact quality indicators and outcomes, such as mortality rates.

Conclusion:

The proposed framework may have beneficial and practical applications. We could use the HCSP formulation to evaluate health technologies that reduce pressure on the healthcare system. This evaluation forms part of the health technology assessment (HTA). The goal of HTA is to guide the efficient use of limited healthcare resources. This becomes crucial in high-strain situations like those seen in the NHS, leading to elective surgery cancellations and potential medical care rationing. Traditional HTA approaches may underestimate HCSP-easing health innovations such as vaccinations. This is because of the large elective care backlogs and the high potential cost of delayed treatment.