The Rising Cost of Medical Interventions

Novel medical interventions have emerged from scientific advancements, offering better quality and extended life for patients with life-threatening conditions. These interventions include gene therapies and tissue-engineered medicines that target various cancers, rare, and ultra-rare diseases. However, the medicines come with an extremely high cost. In 2022, the top ten most expensive medicines ranged from USD 600,000 to over USD 3.5 million per dose. This high cost puts a significant financial burden on households. Consequently, it can reduce, delay, or even deny access to potentially life-saving care.

The Dilemma of High-Cost Medicines

There is currently no universally agreed-upon definition of high-cost medicine. Medicines often get described as those whose Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) goes beyond the public’s willingness-to-pay threshold for a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY). Including these medicines in a public health insurance scheme’s benefits package means a high opportunity cost for a health system. If we increase the budget for public purchase, it results in withdrawing resources from private consumption through taxation or other methods.

The Thai Approach to High-Cost Medicines

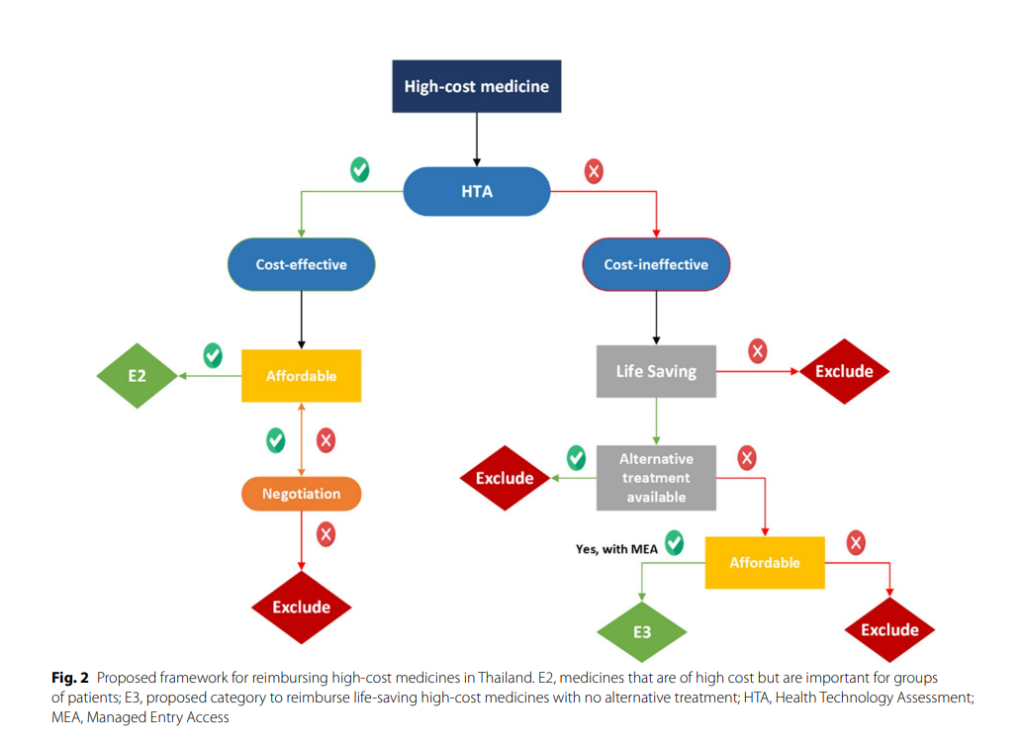

Thailand, an upper middle-income country in Southeast Asia, uses Health Technology Assessment (HTA), including cost-effectiveness analysis, to guide the development of its pharmaceutical benefits package, the National List of Essential Medicine (NLEM). Over the years, there has been increasing pressure to include medicines deemed cost-ineffective. A study was therefore commissioned to provide recommendations for the management of such medicines as part of the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) Benefit Package (UCBP).

International Experiences and Recommendations

The study revealed that countries have established alternative mechanisms for reimbursing high-cost medicines. These mechanisms require particular eligibility criteria to be met, such as disease severity, rarity, the effectiveness of medicines, treatment of a life-threatening condition, and the absence of alternative treatment options. The study also proposed a framework for reimbursing high-cost medicines in Thailand, which involves creating a new sub-category, “E3”, for the NLEM to access high-cost medicine under the benefit package.

Conclusion and Key Message

Public health insurance schemes should only reimburse high-cost medicines when they are cost-effective. Countries may consider reimbursing non-cost-effective high-cost medicines only when they save lives or lack alternative treatment options. Monitoring and evaluation of implementation arrangements will be critical for assessing the impact of these programmes.