Introduction

Traditional cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) has long been a cornerstone in healthcare decision-making. However, its reliance on measures like quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) has faced criticism for excluding additional value dimensions. A recent publication addresses this gap by exploring extra-welfarist (EW) methods to incorporate values beyond just health. The focus was on non-market environments, such as the British National Health Service (BNHS) and similar systems worldwide.

Limitations of Traditional CEA

CEA typically combines health-related quality of life and life expectancy into QALYs, which are then compared with associated costs. This method relies solely on individual utility measures. Similar criticisms apply to EW methods, which avoid using individual utility preferences but still focus predominantly on health. Despite its intent to include broader values, EW has not effectively incorporated gains beyond health due to a lack of clear methodologies.

Expanding Value Metrics in Healthcare

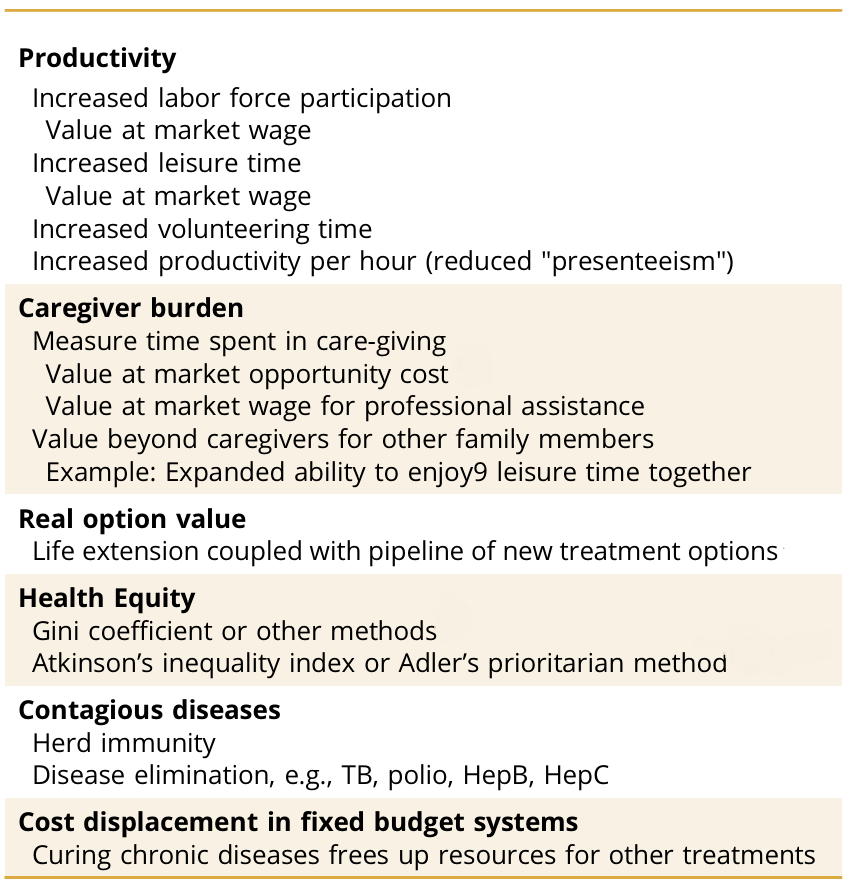

The ISPOR 2018 Task Force introduced the “Value Flower,” which catalogues potential missing value sources. These include health-related gains like productivity, real option value, reduced caregiver burden, and health equity. For example, improved health can decrease caregiver burden, measured by the rate at which burden declines as patient health improves. Table 1 provides examples of these additional values and their measurement methods. These value elements can be characterised as improvement in people’s health or depend on treatment severity.

Table 1. Examples of Health-Related Additional Values and Their Measurement

Budget Allocations and Willingness to Pay (WTP)

The ability to supply additional health comes at increasing marginal cost, influenced by available technologies and their application. Optimality is achieved when marginal cost equals WTP. For example, the BNHS budget for 2022/23 was £181.7 billion. The operative threshold for cost-effectiveness in the UK is closer to £13,000 per QALY, despite higher advertised values. This discrepancy highlights the importance of budget allocations in determining implicit WTP values.

Challenges and Solutions

Numerous conceptual problems remain in incorporating these additional values, such as double counting and assessing WTP. Double counting can be avoided through conceptualisation or statistical analysis. For instance, worker productivity and absenteeism often overlap. Professional judgement is crucial in these cases to ensure accurate valuation without redundancy.

Conclusion

When EW proponents aim to use measures other than individual utility, the only meaningful substitute becomes decision-makers’ willingness to increase healthcare budgets. This approach highlights the importance of societal values and the distribution of benefits. In fixed-budget environments, only the commitment of governments or major non-governmental organisations to fund these extra values can bring them to fruition. When we move from “health” to “welfare” in the measurement of increased healthcare value, we can develop methods with additional values that are truly expanding value metrics in healthcare.