Introduction

Chronic conditions are a growing burden in childhood, affecting 1.7 million children and young people (CYP) in England as of 2018. The UK struggles with chronic disease management, having one of the highest asthma mortality rates in Europe. Inadequate asthma care standards contribute to 46% of these deaths. Poor chronic disease management leads to higher healthcare costs and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in childhood, with long-term consequences for families and society. Furthermore, children with chronic conditions face worse academic performance. The cost to society for caring for preschool children following hospital attendance for asthma or wheeze is estimated at £14.53 million. Of this amount, 76% is borne by the National Health Service (NHS). Therefore, evaluating the cost-effectiveness of integrated care for children is crucial to address these challenges.

Integrated Care as a Solution

Redesigning paediatric healthcare to manage chronic conditions aligns with the NHS Long-Term Plan and policies among high-income countries. Integrated care, which connects primary, community, and specialised services, is proposed to improve chronic disease management. Evidence suggests integrated care may enhance HRQoL, but results on healthcare quality, costs, and cost-effectiveness are mixed. Limitations in current studies highlight the need for further research on integrated care systems for children.

The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership Model

The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership (CYPHP) Evelina London model aims to provide coordinated, biopsychosocial care in primary and community settings for CYP with at least one tracer condition (asthma, eczema, and constipation). Between 2018 and 2021, general practices in Southwark and Lambeth were grouped into clusters and randomised to CYPHP (intervention) or enhanced usual care (EUC, control). The CYPHP practices included local child health clinics, specialist nurse-led services, population health management, specialist team training, and multidisciplinary team case planning, in addition to EUC services.

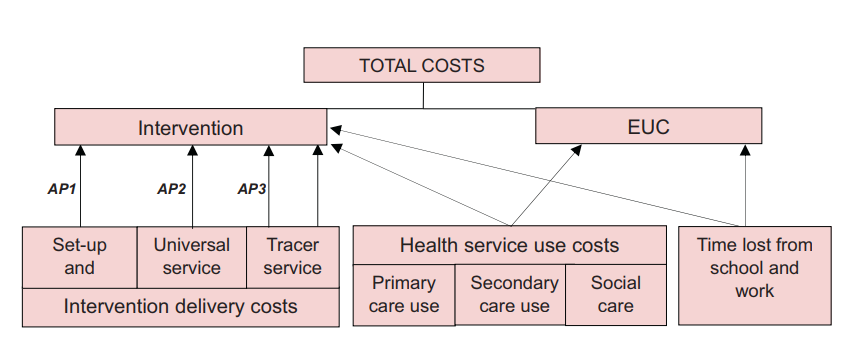

The CYPHP trial involved 97,970 children, including 1,731 participants with chronic conditions. The study used cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and cost-benefit analyses to evaluate the intervention. Researchers conducted these analyses from both the NHS/Personal Social Service (PSS) and societal perspectives. The trial aimed to capture the diverse effects of CYPHP on health outcomes and costs.

Cost-Effectiveness of Integrated Care

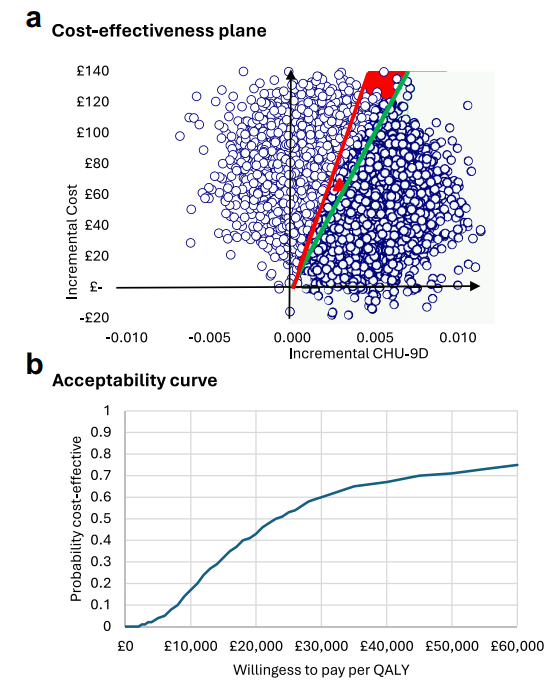

A recent study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of CYPHP compared to EUC for children with severe chronic conditions from both NHS/PSS and societal perspectives, at 6 and 12 months. At the 6-month mark, CYPHP was not found to be cost-effective under both perspectives. Although positive trends began to emerge at 12 months, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) under NHS/PSS perspective was as high as £45,586 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). This value indicates that while the intervention becomes more cost-effective over time, it remains relatively expensive per unit of effectiveness gained.

Furthermore, from a societal perspective—which encompasses the effects on patients, families, schools, and time lost from school and work—CYPHP demonstrated trends towards cost-effectiveness, with an ICER of £22,966/QALY. Also, as shown in Figure 2, the probability of being cost-effective under the societal perspective ranged from 0.4 to 0.6 for willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds of £20,000/QALY and £30,000/QALY, respectively. The cost-benefit analysis indicated a positive net monetary benefit of CYPHP at 12 months.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CYPHP was not cost-effective compared to EUC at 6-month follow-up. However, at 12 months, it shows trends towards cost-effectiveness, particularly under the societal perspective and among children with severe chronic conditions. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects of CYPHP as it becomes more embedded in paediatric healthcare delivery. The positive change in findings between 6 and 12 months suggests that CYPHP may have a beneficial long-term impact on health outcomes and costs.